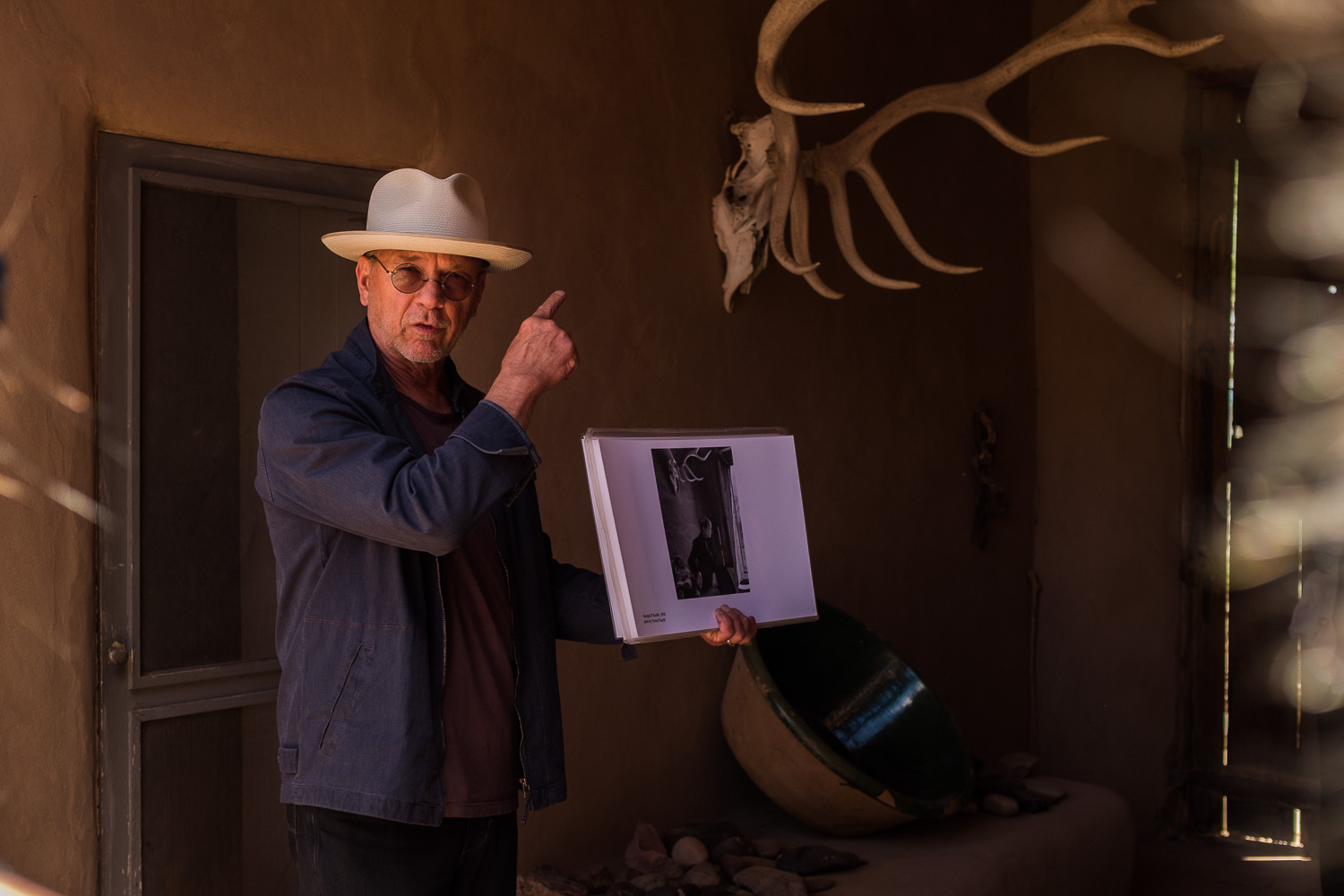

It started innocently enough. At the beginning of the year, my mom and I decided to finally make the pilgrimage to Abiquiu, New Mexico to take a class with our nearest and dearest clay teacher, Debra Fritts. Debra and her husband Frank have a phenomenal home/gallery/studio in the middle of what’s lovingly referred to as O’Keefe Country (Georgia O’Keefe spent some of the last years of her life in an amazing cliffside adobe home in the center of this sun soaked town). It’s scenic and beautiful, a creative’s paradise, and I knew my mom wanted to make the trip but wouldn’t do it alone. So I did it for her. I did it under the guise that I’m always up for an adventure and a plane ride, and if ample photographic opportunities might present themselves along the way…even better.

So we went. We landed and felt the sharp sting of dry noses and the drunken heaviness of the altitude shift. We stopped in Santa Fe for groceries of cheese and apples and rosé, because there are no grocery stores in Abiquiu. We meandered our way through hillside highways to the Airbnb we rented that sat on the bank of the Rio Chama.

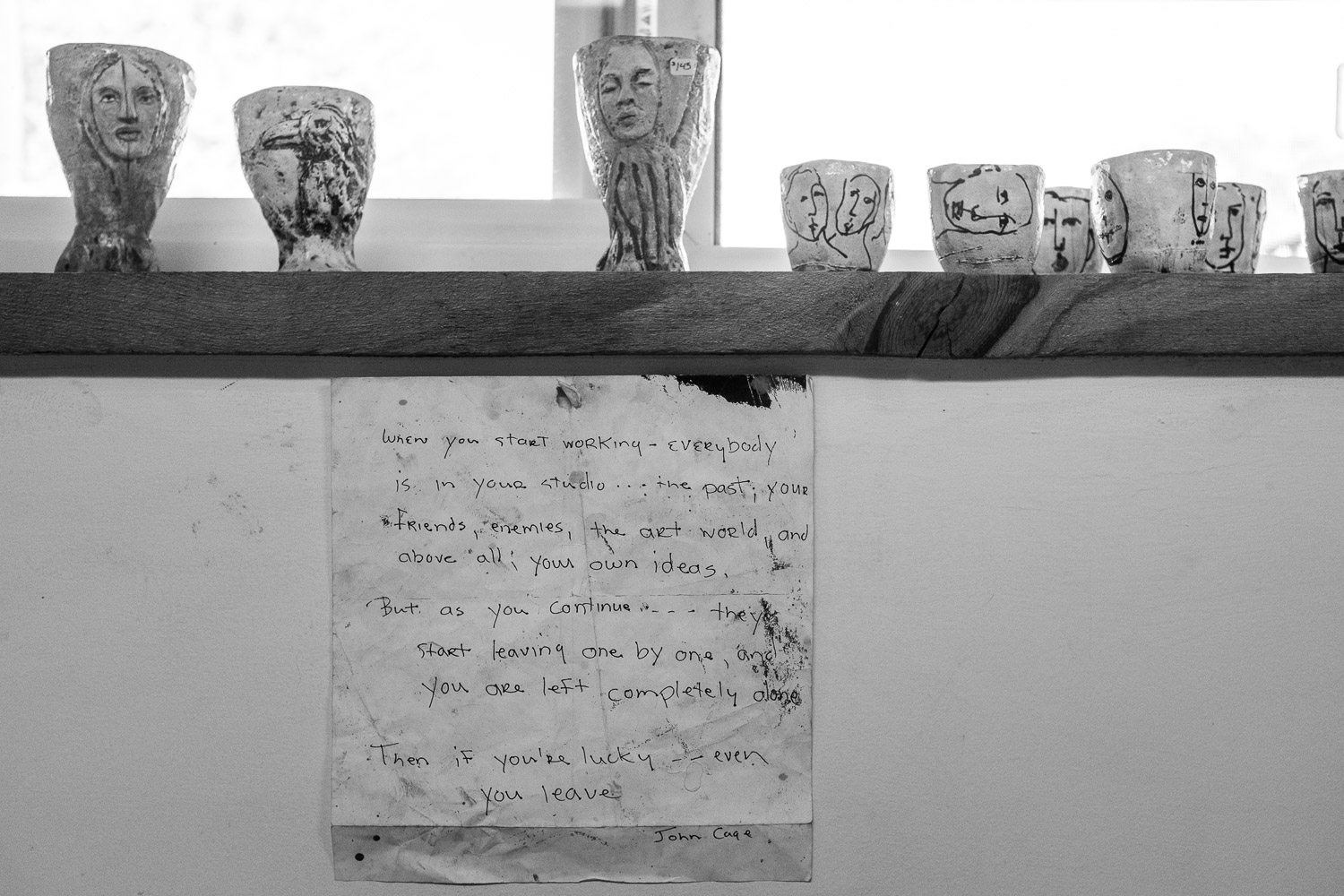

And for five nights we slept with the windows flung open, the sounds coyotes permeating the twilight. We awoke with the sun, and we trekked to Debra’s studio to make our daily peace with the clay. I was excited to be under Debra’s expert care and guidance again, but the clay was just a necessary byproduct. It had been over 10 years since I’d had my hands in anything other than Photoshop and typographic tracing paper. In art school, pressing buttons had become my medium of choice. Getting dirty and being in the mess of artmaking had slipped out of my realm of comfort in exchange for my high school diploma.

But here I was, having traveled across the country to specifically work in clay. I might as well accept my fate and play pretend artist for a few days. Certain my pieces would end up in a dumpster rather than in my carry-on I set to work. Surprisingly, the clay felt oddly comfortable in my hands. The smell of talc and dust greeted me like an old friend each morning. I couldn’t remember all the techniques. The understanding of oxides and firing orders had escaped me, but the way it felt to be here, here in a place I’d never actually been before, was eerily familiar.

On day two, we toured Georgia O’Keefe’s Abiquiu home. Tucked on a hillside overlooking the sharp contrast of orangey valley with a cobalt blue sky, it took my breath away. O’Keefe painted this view, but her depiction was always a little off kilter from the reality. Her explanation? She said she painted not what she saw, but how what she saw made her feel.

And for me, this is where I found myself too. My body and my heart and my creative soul were finding themselves at home here, not because of what they were seeing, but what they were feeling. I was feeling so many things again. Neurons that had been severed with the busyness of college and career-finding and navigating the path to adulthood began to spark again. I was remembering what it was like to get my hands dirty and build from the heart rather than from the brain. I left the studio each day poured out, totally spent, but more alive than before.

In the aimless wanderings that happen when you sit working in the studio, I remembered that this is who I once was, one who makes things. I was the girl who came home from school each day and cut images out of magazines, collected flowers in the yard to press between book pages, and toted around a bucket of crayons, always creating. Somewhere down the line my obligations to my logical self–the one who says the only things that matter are the things you can measure–won out, and my creator self laid down. It was in the stale afternoon air of this desert studio that I recognized perhaps the tugs I’d been feeling in my heart–the restlessness, the struggle for identity and expression–perhaps they were just cries for acknowledgement from a part of myself I’d been ignoring for the last decade.

I went to New Mexico for my mom, for Debra, for the iconic sunsets. I left with dirty hands, a full heart, and an important lesson: we exist as a whole whether we choose to acknowledge the all our pieces or not. We can choose what parts to nourish and what parts to ignore, but it doesn’t mean they’re not there. Life doesn’t create the ideal climate for balance, it’s a life-long struggle, but denying the existence of all of you leads to a mysterious sense of emptiness and longing.

Sometimes you have to leave home to come home to yourself.